When students walk into their first organic chemistry lab, most of them see

“just glass everywhere”. To me, there are really two worlds of glass in that room.

- the familiar beakers and cylinders that look like general chemistry

- the long condensers, three-neck flasks, and odd adapters with ground-glass joints that click together like Lego

- most of that second group is not made in molds like beakers – it’s hand-blown from glass tubing, one piece at a time

If you only remember three things from this article, let it be these:

- Molded glass (like beakers) is great for gentle, everyday use at atmospheric pressure.

- Hand-blown glassware is built for what organic labs actually do: heat, cold, vacuum, and long, connected setups.

- Using “random glass” for high-temperature or vacuum work is how you end up with sudden breakage, solvent showers, and very bad days.

Two ways to make lab glass

1. Molded / pressed glass

Molded (or pressed) glassware is made by pouring or pressing hot glass into a mold. You already know this family:

beakers, graduated cylinders, Erlenmeyer flasks, petri dishes, and general-purpose storage bottles.

For atmospheric-pressure work – weighing solutions, mixing, rough volume measurements – molded glass is perfect:

- cheap and easy to replace

- good enough accuracy for routine volumes

- strong enough for gentle heating on a hotplate or in a water bath

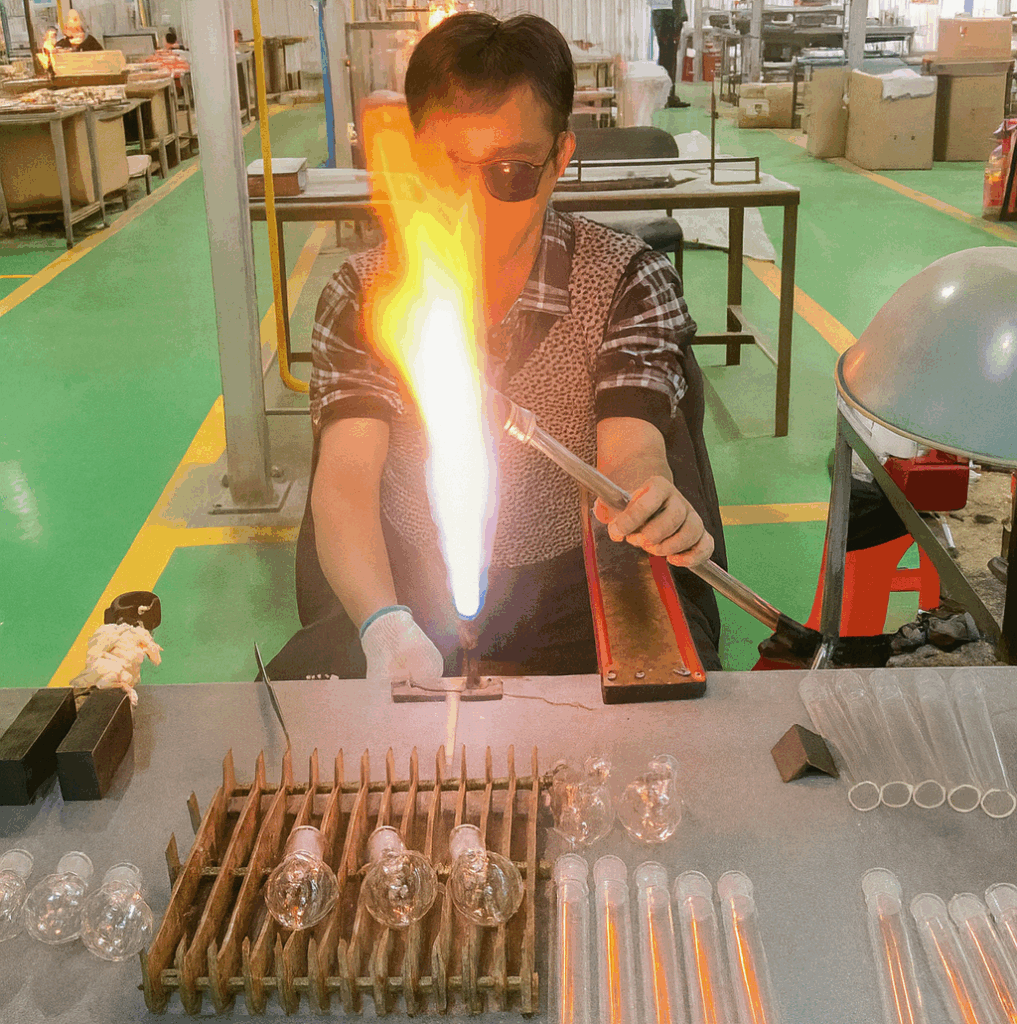

2. Hand-blown glass from tubing

Hand-blown glassware starts from glass tubing and rod. A glassblower uses a flame to:

- heat sections of tubing

- stretch, bend, and flare them

- blow bulbs and flasks

- fuse different pieces together

- add standard taper joints at specific places

What hand-blown glass from tubing is good at

- Complex shapes, no problem. Long condensers, distillation heads, multi-neck flasks and odd angles are much easier to build from tubing than to pour into a mold.

- Wall thickness where it matters. The glassblower can keep the walls more even overall and deliberately leave a bit more thickness in the places that see the most heat or stress.

- Proper annealing. After shaping, pieces are usually annealed so internal stresses relax instead of hiding in the glass.

- Built-in standard joints. It’s straightforward to pull in 14/20, 19/22 or 24/40 joints and side-arms, so the pieces click together into a system.

You do pay for more labour per piece, so the unit price is higher than a simple molded beaker. In return, you get glassware that is

much more flexible for real teaching and research setups and behaves predictably when you start heating, cooling and pulling vacuum.

Complex shapes and controlled flow paths

Think about:

- a Liebig or Allihn condenser

- a Vigreux column

- a Claisen adapter

- a Dean–Stark trap

These are not “just containers”. They are carefully shaped pathways where:

- vapours change direction and condense

- liquid levels collect to a certain height

- flow is controlled through narrow sections

Those shapes simply aren’t practical to make by pouring glass into a mold. They’re born from tubing and flame.

What it looks like when glass fails

From the outside, molded and hand-blown pieces may both look like “just glass”. Inside, they behave very differently once you

start pushing them: longer heating, higher temperatures, vacuum and repeated cycles.

When glass has hidden stress, is too thin in the wrong places, or was never meant for that kind of job, you see things like:

- fine “crazed” crack patterns appearing during or after heating

- sudden star cracks at the bottom of a flask

- implosion under vacuum, especially near joints and sharp transitions

Good hand-blown borosilicate, properly annealed and matched to the task, is not magic – it still needs to be inspected and retired when damaged –

but it gives you a lot more safety margin than random glass of unknown origin.

Different types of hand-blown glassware brands

Once you start shopping for hand-blown glassware, you’ll meet a lot of brand names. Instead of memorising logos, it can help to think in terms of

brand types and what you gain or lose with each.

| Brand type | Typical examples | What you usually get | For university organic teaching labs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-established catalog brands | Chemglass, Wilmad-LabGlass | Very consistent dimensions, broad support for teaching & research, strong warranty and technical documentation | Recommended as a backbone for demanding high-vacuum / high-temperature work if budget allows |

| Value-oriented hand-blown brands | Laboy Glass and similar suppliers | True hand-blown borosilicate with standard taper joints, complete 19/22 or 24/40 sets at a lower price point; product quality suitable for research use and already adopted by hundreds of universities and research institutes. | Recommended as a budget-friendly option for equipping multiple teaching hoods with full organic glassware kits |

| Marketplace-driven “big seller” brands | StonyLab and other Amazon-focused labels | Very wide catalog, aggressive pricing, fast fulfillment through large platforms | Not recommended as the primary supplier for university organic teaching labs; more suitable for low-risk, non-critical uses |

This is not a formal ranking; each type has a place. In practice, many teaching labs mix them: a few high-end pieces where tolerances really matter,

and solid, value-oriented hand-blown glass for the everyday workhorses.

Bringing it back to your own lab

If you are setting up or upgrading an organic teaching lab, the key questions are simple:

- Where do we really need the performance of hand-blown borosilicate?

- Where are molded beakers and cylinders perfectly fine?

- How will we inspect and retire damaged glassware before it fails in a student’s hands?

Answer those honestly, choose glass that matches the job, and a lot of “mystery breakage” and bad days in the hood simply disappear.